From ancient fertility symbols to contemporary digital sculptures, artists have used their skills to explore, challenge, and celebrate what love is and what it looks like. Through symbolism and imagery, love in art is a dynamic force representative of the times—always enduring and transforming.

Love has long been a significant and prevalent theme in the canon of art history. Across cultures and centuries, artists have always sought to capture its essence—how it inspires, torments, and exalts men, women, and even gods. Whether it be a self, affectionate, enduring, familiar, romantic, playful, obsessive, or selfless type of love, exploring this subject has forgone merely depiction. While the act of creating itself is already a declaration of love, material, medium, physicality, and concept have also become vehicles through which ideas or emotions are expressed in visual language.

Rarely are works of art ever straightforward. Often, they include political, social, and personal symbolism. In the same vein, representations of love in art are not created in a vacuum; they are deeply rooted and influenced by the cultural and societal contexts in which they emerge. Consequently, if art reflects society, it can make or break perceptions and challenge norms. Through subtle symbolism or bold statements, art has repeatedly presented and celebrated various perspectives on love and relationships for viewers to reconsider.

The Venus of Willendorf, an iconic piece of portable Upper Paleolithic art dating back between 30,000-24,000 BCE, is one of the oldest and most famous surviving pieces. Its form, suggestive of the process of reproduction and child-rearing, embodies the nurturing aspect of love—a primal connection between human emotion and the perpetuation of life.

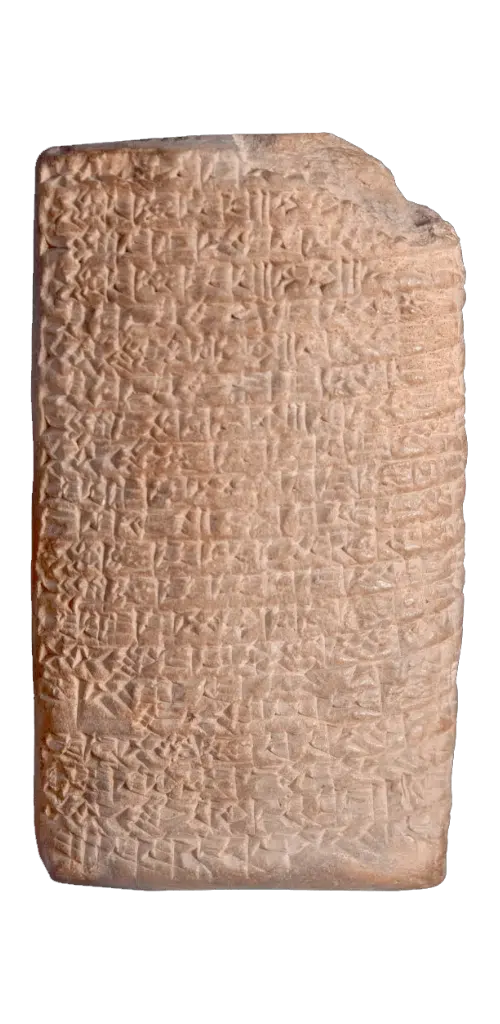

In ancient Mesopotamia, around 2,000 BCE, the Sumerians etched the world’s oldest love song on a cuneiform tablet. The Love Song of Shu-Sin was part of a sacred marriage rite in which the king symbolically marries the goddess of love Inanna through a priestess to ensure fertility and prosperity for the coming year. The poem, spoken in the female voice, is a profoundly affectionate and erotic composition.

“Bridegroom, dear to my heart,

Goodly is your beauty, honeysweet,

Lion, dear to my heart,

Goodly is your beauty, honeysweet.

You have captivated me, let me stand tremblingly before you.

Bridegroom, I would be taken by you to the bedchamber,

You have captivated me, let me stand tremblingly before you.

Lion, I would be taken by you to the bedchamber.

Bridegroom, let me caress you,

My precious caress is more savory than honey,

In the bedchamber, honey-filled,

Let me enjoy your goodly beauty,

Lion, let me caress you,

My precious caress is more savory than honey.

Bridegroom, you have taken your pleasure of me,

Tell my mother, she will give you delicacies,

My father, he will give you gifts.

Your spirit, I know where to cheer your spirit,

Bridegroom, sleep in our house until dawn,

Your heart, I know where to gladden your heart,

Lion, sleep in our house until dawn.

You, because you love me,

Give me pray of your caresses,

My lord god, my lord protector,

My Shu-Sin, who gladdens Enlil’s heart,

Give my pray of your caresses.

Your place goodly as honey, pray lay your hand on it,

Bring your hand over like a gishban-garment,

Cup your hand over it like a gishban-sikin-garment

It is a balbale-song of Inanna.” — trans. Samuel Noah Kramer, History Begins at Sumer, pp 246-247.

A true staple of Baroque sculpture works, Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa was commissioned by Cardinal Federico Cornaro of Venice in 1647. The sculpture is said to be directly inspired by Saint Teresa of Ávila’s writing:

“I saw in his hand a long spear of gold, and at the iron’s point there seemed to be a little fire. He appeared to me to be thrusting it at times into my heart, and to pierce my very entrails; when he drew it out, he seemed to draw them out also and to leave me all on fire with a great love of God. The pain was so great, that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it. The soul is satisfied now with nothing less than God. The pain is not bodily, but spiritual; though the body has its share in it. It is a caressing of love so sweet which now takes place between the soul and God, that I pray God of His goodness to make him experience it who may think that I am lying.” — Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582), The Life of Teresa of Jesus, Chapter 29; Part 17.

Despite controversies over its perceived sexual implications, such that it could be considered “the most risqué of religious sculptures in Christendom,” to deny Bernini’s skill in portraying sensual and extraordinarily lifelike religious ecstasy is blasphemy.

Initially named in French as Les Progrès de l’amour: Le rendez-vous, this Jean-Honoré Fragonard Rococo oil painting is part of a series of four canvases commissioned by Comtesse du Barry, who was Louis XV’s last mistress. The series depicts a persistent suitor courting a potential match and ultimately winning her favor, making it renowned as one of the most compelling representations of love in art history. Despite its grandeur and significance, Madame du Barry rejected the canvases for unknown reasons. However, it is believed that the most likely reason was how much of herself she could see or knew others would see on the canvases.

In the 1890s, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec became captivated by the Parisian nightlife of the urban underclass and dedicated time to painting everyday scenes in brothels. In Bed, The Kiss is of two women sharing a passionate kiss under the sheets and is just one of the many drawings and paintings that offers a glimpse into the private, intimate moments of the women of the night in and out of their work. The paintings demonstrate a close observation and compassion towards the women, without any hints of sensationalism or voyeurism.

When Serbian and German performance artists Marina Abramović and Ulay first met in 1976, they became inseparable and began performing together, referring to themselves as a “two-headed body.” Their ultimate collaboration, announced in 1983, was called The Lovers. The idea was to be the first people to walk the Great Wall of China, starting from opposite ends and meeting in the middle to marry. However, due to extensive paperwork and communication with the Chinese government, the performance did not occur until 1988. On March 30, 1988, Abramović and Ulay began their walks from opposite ends of the Great Wall. After 90 days, covering about 2,000 km each, they met and embraced at the center of a stone bridge in Shenmu, Shaanxi province. Despite the preparation and anticipation of a wedding, none took place. Following a press conference in Beijing, they returned separately to Amsterdam and didn’t meet or communicate for 22 years. Ultimately, the performance art piece is an exploration of love, separation, and reunion. It also underscores the idea that love can lead to personal transformations, emphasizing that individuals may evolve and not remain static throughout the course of a relationship. The impact of love is seen in the union at the center of the Great Wall and in the realization that, at times, the person you become may differ from the one who embarked on the journey.

Félix González-Torres’ “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) consists of two identical commercial wall clocks installed side by side and set to the same time, but gradually falling out of sync due to battery depletion and the inherent nature of their mechanisms. Since its creation in 1987, the artwork has been replicated and featured in over 75 exhibitions with the artist providing specific parameters to be followed when displaying the work. Many have interpreted the work to be a commentary on Ross Laycock’s, González-Torres’ partner, struggle with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and the broader theme of mortality. In a letter sent to Laycock in 1988, González-Torres showed a rough sketch of the piece, entitled merely Lovers. In the letter, he contemplates:

“Don’t be afraid of the clocks, they are our time, the time has been so generous to us. We imprinted time with the sweet taste of victory. We conquered fate by meeting at a certain time in a certain space. We are a product of the time, therefore we give back credit where it is due: time. We are synchronized, now forever. I love you.”

Gerhard Richter’s artistic repertoire is marked by its diversity, showcasing his ability to navigate various styles and mediums. Widely regarded as one of the most important and influential living contemporary artists today, Richter has consistently pushed the boundaries of artistic expression from his abstract compositions to meticulous photorealistic renderings. In S. mit Kind, as is the case with all his photo-paintings and overpainted photographs, Richter considers the nature and significance of the photograph and its subject. Richter writes:

“Blurring is not the most important thing; nor is it an identity tag for my pictures. I blur things to make everything equally important and equally unimportant. I blur things so that they do not look artistic or craftsmanlike but technological, smooth, and perfect. I blur things to make all the parts a closer fit.”

Known alternatively as Flower Thrower, Banksy’s Love Is In The Air portrays a radical youth complete with a backward baseball cap and a bandana concealing the lower half of the face. Positioned mid-motion, the figure appears to be launching a bouquet reminiscent of throwing a grenade or Molotov. Despite the aggressive stance, the intent is to propel a universal symbol of love and peace rather than a weapon. This piece is a testament to Banksy’s distinctive artistic style and potent political activism, embodying a plea for peace.

The inception of Love Is In The Air can be traced back to 2003, when Banksy first created this image on the Beit Sahour, near the Israeli West Bank Barrier, a structure spanning over 700 km that separates Israel from the West Bank. Since its initial appearance, the artwork has assumed various forms, including street art, painting on canvas, and screen prints. In each iteration, Love Is In The Air remains a compelling call for peace, showcasing Banksy’s commitment to using art to advocate for peace and equality.

Dior’s J’adore parfum was described as “what solid gold would smell like if it had a scent.” 25 years later, the French multinational luxury fashion house collabs with Turkish-American new media artist and designer Refik Anadol to celebrate the iconic fragrance, an olfactory work of art born of Christian Dior’s passion for flowers. The result of this collaboration is a mesmerizing artwork rooted in data from the floral composition formulas of Dior’s latest fragrance, L’Or de J’adore, by Francis Kurkdjian. J’ Adore — AI Data Sculpture, featured in The Dior J’adore exhibition, showcases dynamic, liquid gold patterns generated by Anadol’s studio’s custom Generative AI algorithms. The work is a cross-modal experience where the fragrance of L’Or de J’adore’s flowers undergoes a transformation through algorithms into a digital visual sculpture—a way of making “the invisible visible.”

From ancient fertility symbols to contemporary digital sculptures, artists have used their skills to explore, challenge, and celebrate what love is and what it looks like. Much like art, love is unquantifiable. Many have tried, as evidenced by art history. Through symbolism and imagery, love in art is a dynamic force representative of the times—always enduring and transforming.

0 thoughts on “The Language of Love in Art: Decoding Symbolism and Imagery”